“A militant pulled my newborn from me.”

Inside the lives of women displaced by war in Sudan

When paramilitary forces entered the city of Geneina in West Darfur, Sudan, in 2023, people fled for their lives – but not 41-year-old Daralssalam. She was nine months pregnant, and the baby was coming. She went into labour by the side of a road.

The militants “saw no difference between men, women or children,” Daralssalam says, crying as she recalls the incomprehensible violence she witnessed. “Everyone was getting killed or raped.”

As she gave birth, fighters surrounded her. “A militant pulled my newborn from me, severing the umbilical cord,” she says. They parted the newborn's legs to check the genitals. “They said if it was a boy, they would kill him.” Fortunately the baby was a girl, whose life was spared.

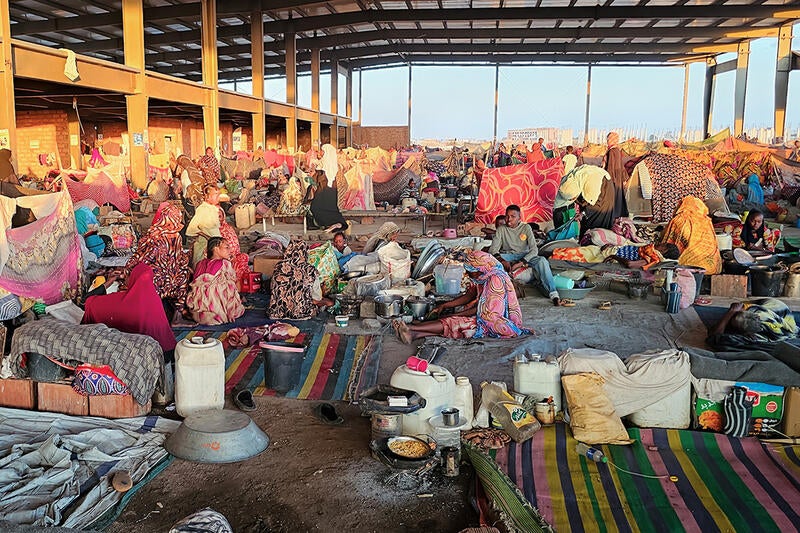

The war, which began when armed conflict erupted between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces (RSF) in April 2023, continues to rage, displacing more than 12 million people. UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive agency, went inside the sprawling displacement camps in Sudan, as well as in Chad and the Central African Republic, to learn the stories of life amid war for women and girls.

A mother of five, Daralssalam recalls a typical morning for her family before the fighting began: “We would eat breakfast together before heading off to school and work.” For Daralssalam, this meant going to teach at a university. Now the family is fractured – three children are with her in Chad, but the rest of the family is missing. Daralssalam was separated from her husband and other children amid the chaos.

“In one day, everything changed.”

The conflict has created the largest displacement crisis in the world. Women and girls are trapped in a relentless nightmare of violence, hunger and disease.

Souat, 39, witnessed atrocious crimes targeting civilians in her hometown of Geneina. “We suffered from heavy gunfire,” she says. “Over 50 families were killed in one day. We collected their bodies in sacks and buried them. After that, RSF positioned snipers all over the city; we couldn’t even go out to get food or water. Many houses were burned down. When we fled Geneina, we thought that was going to be our last day alive. On our journey, we saw women with broken limbs and children of just four or five years of age, with their legs or hands cut off.”

Around 8.8 million people have been forcibly displaced within Sudan. Fatima is among them. Now staying at the Tawila camp in North Darfur, she used to work at the El Fasher South Hospital.

“Then the hospital was attacked, and snipers were positioned on our roof. This forced us to evacuate,” she says. “Some of our colleagues lost their lives in the attack, one from our hospital and another from El Fasher Maternity Hospital.”

In January 2024, a drone strike on El Fasher Maternity Hospital killed 70 patients; the United Nations remains deeply concerned for civilians in the area.

In addition to the millions displaced within Sudan, some 3.6 million people have fled to neighbouring countries.

Souat (above left) becomes emotional as she speaks about how hard life is for refugees at the Farchana refugee camp in Chad. “The needs are so high,” she says. “We need everything: an ambulance, clinics, medical supplies, food and water. If you don’t eat, you die, right? We need to stop child marriage and prevent women being attacked in the camp. We lost our homes, our families – everything. We have nothing. We need much more humanitarian help.”

Women and girls make up around half of the displaced people in the Central African Republic.

Sexual violence has become the depraved hallmark of the war in Sudan. Many women and girls have been and continue to be subjected to rape, abduction and forced marriage. In the second half of 2024, there was a 400 per cent increase in people seeking gender-based violence response services in Sudan.

UNFPA is working tirelessly to meet the needs of women and girls who have survived rape and other horrific ordeals. At safe spaces and clinics in Sudan and neighbouring countries, UNFPA partners are providing physical and emotional support for survivors, including the clinical management of rape, counselling and psychosocial support, including peer support.

But UNFPA staff members are struggling to handle the demand for services. Much more humanitarian assistance is needed to address a crisis of this scale.

The struggle does not end when women and girls arrive at a camp. “Life in this camp is dangerous for women,” says Mariam, 32, of the Korsi camp. Like many other women looking for work to help feed their families, she has faced a “choice,” she says: “Work for someone who will only hire you if they can take advantage of you, or let your children go hungry.” When Mariam’s husband was killed in Sudan, she became the sole provider for their seven children.

UNFPA support is designed not only to help survivors of gender-based violence access support and services, but also to mitigate risks and teach skills to help women reclaim some independence. For instance, at the Korsi camp which is close to the town of Birao, income-generating activities, such as learning baking and sewing skills, enable women to set up stalls in town and be their own boss.

Nadine, 25, is a UNFPA-supported midwife working at the Birao health clinic in the Central Africa Republic. The clinic, near the Korsi camp, provides free services for refugees. UNFPA funds the salaries of a midwife and a nurse, who provide holistic sexual and reproductive health and gender-based violence care and are trained in dealing with obstetric complications.

In Sudan, midwives are working overtime to deliver babies safely. At the Gedaref Maternity Hospital in the east of the country, the work has tripled for midwife Makboula. “Before the war, we used to receive 10 to 12 deliveries per day. Now, we are delivering more than 35 women daily,” she says, due to the migration of people from more dangerous parts of the country. “I feel tired, but I forget my exhaustion when I see a new baby being born."

Until there is peace in Sudan, it is unsafe to return home, and displaced mothers will be raising their babies in far-flung tents. UNFPA, its partners and teams of specialist midwives and gender-based violence specialists are determined to continue to protect and provide for women and girls living in limbo.

So much more is needed to prevent avoidable suffering, and yet, at a time where we need to increase the pace, UNFPA’s humanitarian response is facing uncertainty. Cuts to programmes, due to United States funding being suspended or withdrawn, would be devastating for women and girls impacted by this conflict. UNFPA remains resolute in its efforts to meet the needs of displaced women. The consequences of losing access to vital services are unthinkable.