News

This Valentine's Day, busting 5 common myths about child marriage

- 14 February 2025

News

UNITED NATIONS, New York – “I was married at 14, and I lost my first child at 16 during pregnancy,” Ranu Chakma told UNFPA, the United Nations sexual and reproductive health agency. Child marriage is common in her village of Teknaf Upazila, on the southern coast of Bangladesh – even though it is illegal and a human rights violation.

On Valentine’s Day, UNFPA is urging countries to say “I don’t” to child marriage, a practice that is almost universally condemned, and yet which remains widespread globally. Today, almost one in five young women were married off while still children.

Below, we delve into five common misconceptions about child marriage, and highlight the need for action at all levels.

Child marriage is banned under many international agreements, from the Convention on the Rights of the Child and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women to the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development in 1994. And still, there are 640 million women and girls in the world who were child brides – with more child marriages taking place every day.

How is that possible? Many countries ban child marriage in principle, but define the permissible age of marriage as something other than 18, or permit exceptions with parental consent or under religious or customary law. And in many cases these marriages, and marriages in general, are not legally registered, making enforcement of the law difficult.

But addressing child marriage requires more than laws – it requires rethinking how society values girls.

Programmes like Taalim-i-Naubalighan, in Bihar, India, where two in five children marry before age 18, are having an impact. These programmes encourage young people to think about topics such as gender roles and human rights.

“That's why I was able to help my sister,” said Altamash, a male student whose sister wanted to avoid child marriage and continue her studies. “When I understood her desire and how it would help her, I advocated for her to my father. She is now going to complete her education, and I am so proud of her.”

Child marriage remains pervasive in part because it is seen as a solution to other problems. In humanitarian crises, child marriage rates often rise, with parents believing marriage will secure a daughter’s future by making a husband responsible for economically supporting her and protecting her from violence. Child marriage is seen as a solution that will preserve the honour of a girl and her family after – or in some cases before – she becomes pregnant. In fact, in developing countries the majority of adolescent births take place within a marriage.

Yet child marriage is not a real solution to any of these issues. Child marriage itself leads to girls experiencing high levels of sexual, physical and emotional violence from their intimate partners. And pregnancy is dangerous for girls; complications of pregnancy and childbirth are one of the leading causes of death among adolescent girls. Child brides and adolescent mothers are often forced to drop out of school, upending their future prospects.

Nicolette, 16, in Madagascar was so accustomed to seeing her classmates disappear from school after marrying and becoming pregnant, she never thought to question the practice. That’s until she attended a UNFPA-supported awareness session. “I didn't know that we could be victims of child marriage,” she said. But now, she wants all the girls in her community to know: “Everyone has the right to realize their ambitions, and marriage is a choice!”

Child marriage may sound like a problem of the past, or of faraway places, but in fact it remains a serious threat to girls around the world.

While global child marriage rates are slowly falling, the places with the highest rates also have the most population growth, meaning the absolute number of child marriages is expected to increase. And the problem is global: The largest number of child brides live in the Asia and Pacific region, the highest rate of child marriage is seen in sub-Saharan Africa, and lack of progress in Latin America and the Caribbean mean that this region is expected to have the second highest prevalence of child marriage by 2030. Yet the issue is not limited to developing nations: It takes place in countries like the United Kingdom and United States, too.

“I was basically introduced to somebody in the morning, and I was forced to marry him that night,” Sara Tasneem told UNFPA, recalling her marriage, first an informal spiritual union at age 15, then legally at age 16. “I got pregnant right away, and we were legally married in Reno, Nevada, where it only required permission signed by my dad.”

To change this, we must accelerate our actions to end child marriage – especially by empowering girls. “I was 13 years old when my father gave my hand in marriage to a cousin,” 16-year-old Hadiza, in Niger, told UNFPA. Fortunately, she had access to a safe space through a UNFPA-supported youth programme. “I spoke to a safe space mentor, who, with the help of the neighbourhood chief, negotiated with my parents to postpone the wedding.”

Today, Hadiza is an apprentice to a tailor, learning the skills to become economically self-sufficient. “And in three years I plan to get married to the man I love,” she said.

Child marriage is sometimes misrepresented as a religiously or culturally mandated practice. But there are no major religious traditions that require child marriage. In fact cultural and religious leaders around the world often take a strong stance against child marriage, especially when provided evidence about the consequences of the practice.

“We have always taught young people that, both religiously and legally, it was not advisable. We also explained to those young people that they had to accomplish other tasks, primarily concerning their education, before thinking about starting a family,” Shirkhan Chobanov, the imam of Jumah Mosque in Tbilisi, Georgia, told UNFPA in August.

UNFPA works with faith leaders around the world who are working to end child marriage, including priests, monks, nuns and imams.

“We are seeing very good results as far as warding off child marriage is concerned,” said Gebreegziabher Tiku, a priest in Ethiopia.

While the vast majority of child marriages involve girls, boys can also be married off.

Globally, 115 million boys and men were married before age 18, according to 2019 data, with the highest averages seen in Latin America and the Caribbean. These unions are also linked to early fatherhood, constrained education and reduced opportunities in life.

Still, girls are disproportionately affected by the practice, with about 1 in 5 young women aged 20 to 24 years old married before their 18th birthday, compared to 1 in 30 young men. Child marriage rates for boys are very low even in countries where child marriage among girls is relatively high.

No matter the gender of the child affected, nor the country in which the union takes place, child marriage is a harmful practice that requires addressing a common set of root causes, including economic inequality, limited access to sexual and reproductive health services and information, and factors such as conflict. And one of the biggest root causes, gender inequality, requires urgent and renewed focus.

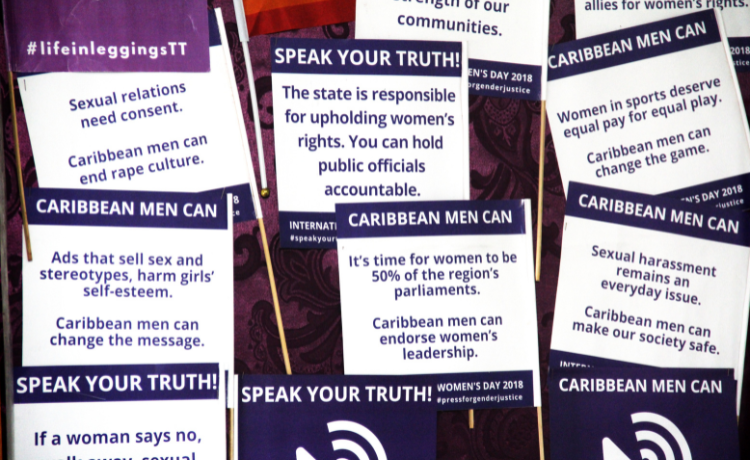

“While we have abolished child marriage, we have not abolished predatory masculinity,” said Dr. Gabrielle Hosein, director of the Institute of Gender and Development Studies at the University of the West Indies, in Trinidad and Tobago, shortly after that country had outlawed child marriage.

Kevin Liverpool, an activist with the advocacy group CariMAN, said men and boys have a critical role to play. “It’s important to raise awareness among these groups, among these individuals, about what feminism is, why gender equality is important for women, but also for men and for all of society,” he said.