News

In Sudan: Changing Labels, Changing Lives

- 15 June 2012

News

Ghalfa, the Sudanese word describing a girl who has not had her genitals ritually cut, carries connotations of impurity, promiscuity, even prostitution. For many years, the social stigma attached to this word helped keep female genital mutilation or cutting alive in Sudan. Despite efforts to end the practice, prevalence among young girls has declined only slightly from 92 per cent in 1990 to 89 per cent in 2006, the latest year for which data is available.

But reframing the conversation about girls' bodies is changing perceptions and practices regarding this traditional practice in Sudan. This was one of the projects reviewed at the 5th Annual Strategic Review Meeting of the UNFPA-UNICEF Joint Programme on Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting held in Saly, Senegal last week. It was also featured in the recently released 2011 Annual Report on the joint programme.

Following consultations with activists, communications experts, academicians, linguists, poets, religious scholars, community members and development professionsala, Sudan’s National Council on Child Welfare and its National Strategic Planning Centre came up with a new strategy to spur collective behavioural change within communities.

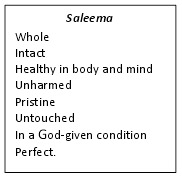

They encouraged the use of the word Saleema – an Arabic woman’s name that means whole, intact, healthy in body and mind, unharmed, pristine, untouched, in a God-given condition, perfect – to replace the negatively charged ghalfa. The idea was to reinforce the idea that being uncut is a natural, desirable state. Rather than trying to discredit a long-held tradition, the strategy aims at allowing new social norm to take its place.

“The Saleema Communication Initiative recognizes a serious language gap in Sudanese colloquial Arabic,” says Samira Ahmed, Child Protection Specialist for UNICEF, Sudan. “Despite more than 30 years of activism to increase awareness of the harm caused by FGM/C, there was still no positive term in common usage to refer to an uncircumcised woman or girl. In contrast, words describing circumcised girls or woman were wholly positive. Once this problem was recognized, it became clear that focusing on language was critical.”

Giving a word new meaning

Curbing FGM/C requires more than changing its label. Beginning in 2008, local activists and members of the media in all of Sudan’s 15 states were trained to explain the consequences of FGM/C, and community networks were established to conduct the nationwide campaign, which was officially launched in January 2010.

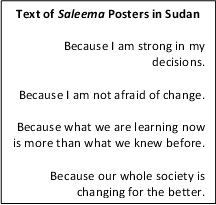

The Saleema message is carefully positioned and branded in the local culture through song, poetry and TV animations, all imbued with a specific palette of colours – mainly orange, red, yellow and green – which are also featured on promotional products including pottery, banners, tablecloths and posters containing specific messages. Colorful clothing, such as women’s dresses and headscarves and men’s scarves, enables both men and women to support the Saleema campaign, showing that they are committed to abandoning FGM/C and proud of it. In four different radio scripts and an animated video, the campaign links traditional values of honour and purity to a new image of the uncut girl as pure and complete.

640 communities have embraced Saleema

Today, some 640 Sudanese communities are involved in the Saleema campaign, up from 450 in 2009. Each community has as many as 30 active networks – of youth, women, children, leaders, religious scholars, legislators and media representatives – who are key to disseminating the Saleema concept. The government is also involved through the NCCW at both the national and state levels, and through state ministries of welfare. The breadth and intensity of community activity in the Saleema campaign often spurs the involvement of legislators and government officials who see it as a path to public support. Many government physicians, aware of the harm inflicted on girls and women by FGM/C, have also joined the campaign and are especially influential in supporting its objectives. Others have rejected the practice after learning from religious scholars that it is not linked to, or required by, Islam. In West Kordofan, after the entire community renounced FGM/C, the local commissioner petitioned the authorities to change the name of the village to Saleema.

Born Saleema in hospitals and clinics

In early 2011 the Khartoum State Ministry of Health, in collaboration with the NCCW and UNICEF, launched a programme called Born Saleema to apply the Saleema approach directly to protecting newborn baby girls. Women who give birth to girls in each of three public maternity hospitals and six health centres are registered and visited by trained health workers who explain the Saleema philosophy – “Every girl is born Saleema; let her grow up Saleema.” Counseling about the benefits of Saleema is provided to parents and family members (with a pictogram information kit for the illiterate) and the family is invited to join the campaign.

Born Saleema families sign a pledge that is prominently displayed at the hospital. The participating hospitals and health centres proudly display Saleema materials inside and outside of their buildings. Once mother and baby leave the hospital, each registered Saleema family is monitored through home visits by health workers.

"The Joint Programme is the main source of funding for Born Saleema and illustrates the holistic approach and social norms perspective of the Joint Programme, " said Nafissatou Diop, who heads the UNFPA/UNICEF Joint Programme on FGM/C. "Under review for possible development in other Sudanese states it is expected that the success of the campaign in Khartoum State will lead the way for integration of the programme into all of Sudan's reproductive health services."

Saleema Ambassadors is another innovative facet of the Saleema campaign. In it, 10 public figures and local celebrities (men and women) each make 10 public appearances – sometimes on national or state television – wearing the Saleema colours and talking about their commitment to Saleema. Rather than instructing audiences on what they should or should not do with respect to FGM/C, the Ambassadors simply tell their personal stories about how they came to embrace the Saleema idea.

The Saleema approach has attracted interest from other East African countries – Eritrea, Kenya and Djibouti – and Sudanese advocates have visited Egypt to share its lessons.

-- Kristin Helmore