News

Indigenous men advocate gender equality to benefit women – and men too

- 12 January 2024

News

COMARCA NGABE BUGLE, Panama – Gender inequality is pervasive everywhere. Globally, 9 in 10 people around the world, both women and men, continue to harbour gender biases, according to a recent United Nations report. These norms harm women and girls – but they are also detrimental to men and boys.

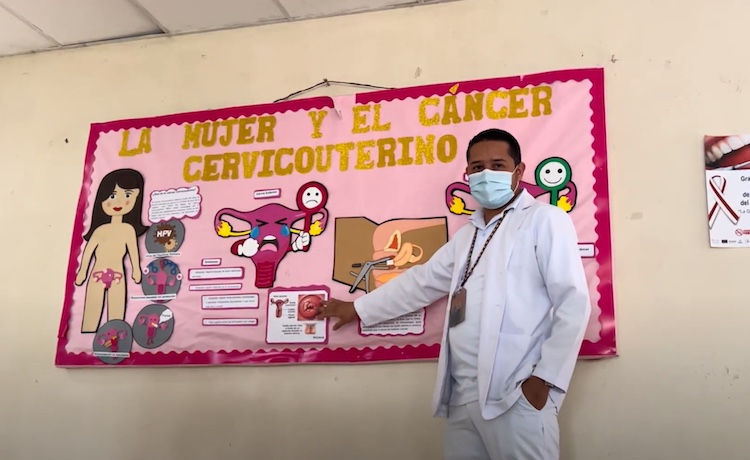

This fact is especially apparent to male health workers in the remote indigenous Ngäbe community of Panama. There, Ngäbe health workers like Dr. Orlando Lopez describe seeing alarming health outcomes for women and men, consequences of both the community’s marginalization and rigid gender norms.

“We have communities that have to walk for two days to reach a clinic”, Dr. Lopez explained. Only a few paved roads wind through the mountainous terrain and local minibuses are infrequent, leaving most people to walk.

But their isolation is not just geographic; it is economic as well. A long history of racial discrimination against the Ngäbe – including barriers in the formal labour market – have contributed to extreme poverty.

When gender inequality is added to the mix, the hardships only escalate.

Poverty, discrimination, machismo

“The men here have a very great power over the women,” explained Humberto Rodríguez, a nurse at the Hato Chami clinic, high in the mountains.

Many Ngäbe men are migrant labourers, harvesting coffee along the border between Panama and Costa Rica, work that takes them away from home for months every year. When the man of the house is away, women do not have the authority to hand over child-care responsibilities to another adult, even if they go into labour and face complications. “The husband is not at home at that moment and the decision is not hers,” Nurse Rodríguez said.

Gender inequality is, of course, not unique to the Ngäbe. But the isolation and extreme poverty already experienced by the community amplify the repercussions. “Unfortunately, we have had many maternal deaths specifically because the husband wasn’t there,” Nurse Rodríguez added.

But men, too, are affected by such norms. For example, Dr. Lopez emphasized that men often refuse health care, with terrible consequences for their well-being. “How come our health care-seeking population is more female?” Dr. Lopez said. “Men come only when they are really dying or because of an accident. They just don't visit health centres.”

Embracing fatherhood – and progress

Resistance to women’s empowerment can, in some cases, be extreme. If a woman chooses to engage in family planning without her partner’s permission, “when he finds out, it can trigger some type of violence,” Dr. Lopez said.

But more commonly, it is a matter of accepted norms, with men being unquestioned decision-makers, even over women’s bodies and health. “There are also problems when a woman should get a Pap smear,” Nurse Rodríguez said. “Sometimes they’ll say, ‘No, I don’t want you to go to the health centre because you will get your Pap exam.’ This is the machismo of men.”

This is where positive role models are making a difference.

Nurse Rodriguez tries to engage with the partners of his pregnant patients – not only for the sake of the women but also for the men, to help them embrace the joys and responsibilities of fatherhood. “We have tried to include the father during pregnancy check-ups and childbirth,” he explained. “We place the baby into his hands because the attention is immediate. ‘Look, you have to take care of him, learn to change a diaper, you have to help the mother.’”

Dr. Jaime Castillo works at the Hato Chami clinic with Nurse Rodríguez. He makes it a point to engage with men when he attends to pregnant patients, new mothers and women seeking contraception. “You have to love her as your equal, not have her as if she were an object that is your property,” he tells the husbands.

Advocates say attitudes are indeed changing.

“Men are realizing that, on their limited salaries, things are more affordable for them” if they support women’s use of family planning and if they support women’s economic empowerment, explained Gertrudis Sire, president of the Ngäbe Women's Association, which empowers women and also engages with men in the community. “There are men who overcome [machismo], but you have to talk to them a lot, guide them…Participation in men's talks is also very important for us because it helps men communicate better. ”

Ngäbe men like Dr. Castillo and Dr. Lopez point to their own fathers as inspiration.

“I grew up in a family where my father placed a lot of value on my mother and the daughters of our family,” Dr. Castillo said. This is, he highlighted, “reality as it should be.”