News

Former Fistula Patient Preaches Prevention to Village Women in Niger

- 15 January 2007

News

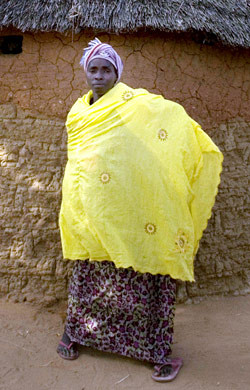

ZINDER, Niger — Kouboura Moutari greets visitors to her home in the village of Madara with her fist raised in a power salute. Unlike most village girls, she is boldly confident when she speaks, with her head held high, her posture erect, and plenty of eye contact.

To see her today, one would never realize the suffering Kouboura has endured. She was married when she was just 15 years old and soon after delivered her first stillborn child. When her second child was due, she laboured for two days before her family brought her by horse and cart to the hospital for a Caesarean, but it was too late and she lost that baby, too.

“It took too long,” remembers Kouboura, sitting in front of the thatch hut she shares with her family. “When it was done, I realized that I couldn’t control it. Urine was just flowing out of me.”

Kouboura had suffered a fistula, a hole in the birth canal that can lead to chronic incontinence. A simple surgical procedure can repair the injury, with success rates as high as 90 per cent. Unfortunately, the price tag of about $300 is out of range for most fistula patients.

Kouboura was one of the lucky ones. She was operated on and the uncontrollable flow of urine stopped.

When Kouboura became pregnant with her third child, she went to have a prophylactic Caesarean. Her labour started on the way to the hospital. After the three-hour cart ride, she delivered a healthy baby girl, but suffered another fistula, and was ultimately repaired again. Now 25 and fistula-free for eight years, Kouboura Moutari begs her parents’ pardon for not remarrying and giving them another grandchild.

“When I go to a Baptism, I am sad not to have another baby,” she says. “But I don’t want to marry. I’m afraid to fall pregnant and suffer again.”

Kouboura’s ordeal has not been in vain. Today, she serves as an advocate for women in Madara and surrounding villages on the importance of prenatal care and seeking medical intervention in time to avoid injury.

“I tell them they need to give birth in good conditions and avoid a long labour,” she explains. “I tell them what I have been through so they don’t have to suffer like I have. Women come crying to me. I advise them not to cry, because they can be cured.”

Kouboura is working with Solidarity, a non-governmental organization working for the prevention and treatment of fistula and the reintegration of fistula patients into their communities, with support from UNFPA, the United Nations Population Fund.

“It’s a problem of changing people’s mentality, which many find difficult to accept,” says Hadizatou Ibrahim, Vice President of Solidarity. “It’s a difficult path to change people’s mentality, but we will do it.”

Sensitization about fistula prevention and treatment is key, according to Issa Sadou, programme officer in charge of Gender and Fistula for UNFPA Niger. UNFPA-supported agents go door-to-door to explain the importance of prenatal care and identify women who may be at risk of suffering a fistula. Community radio programmes and advocacy announcements also are broadcast in five local languages: Hausa, Pular, Zarma, Tamasheq and Gulmanceba.

Dr. Lucien Djangnikpo is the President of Solidarity and the director of the maternity ward at the Central Maternity Hospital, which is housed in the same compound in Zinder. He was trained in Katsina, in neighbouring Nigeria, on the surgical techniques of fistula repair.

“Not very long ago, we thought that fistula was something that couldn’t be cured,” says the mild-mannered doctor. “Now we have treatment, and more importantly, there are many who come back for prenatal care and Caesareans. That is what gives us hope.”

Walking around the grounds of Solidarity, one is struck by its pristine condition. There is no smell of urine or faeces wafting through the grounds. The women who are waiting to be operated on or recovering seem happy and productive, preparing meals, making soap or simply chatting and singing together.

Patients remain at the centre for approximately six weeks for treatment and recovery before being reintegrated into their communities. Since 1998, more than 650 women have been treated. All those working at the centre are volunteers.

Ms. Ibrahim, of Solidarity, says that many of the patients have been living with the condition for 10 years or more and have become “practically crazy being isolated for so many years. Their husbands reject them.” Seeing their suffering compelled her to volunteer at the centre, she adds.

“I am a woman; I am a mother,” she explains. “You see a woman sitting in urine – a woman who needs her dignity – really you must help these women.”

Dr. Lucien agrees that seeing the transformation of the women from victims to survivors motivates him in his work.

“My colleagues who are doctors don’t understand why I do this,” he says. “I am proud to see women who have lost their dignity, their husbands, their families; I am proud to see them regain their dignity, their reproductive health and have another child. There isn’t a salary that can pay for that.”

There are a variety of reasons for the country’s high rate of fistula, says Niger’s Health Minister Mahamane Kabaou. The Government is working to curb early marriage. Thirty-six per cent of girls ages 15-19 in Niger have either been pregnant or are expecting or have at least one child. Illiteracy among women is as high as 91 per cent.

Niger is among the poorest countries in the world, ranking lowest on UNDP’s Human Development Index for 2006. Approximately 61 per cent of the country’s 13 million people live on less than $1 a day.

Transportation is also an issue in a country that is two-thirds desert and where 85 per cent of the population live in rural areas. Girls or women, who may have undergone days of protracted labour, may only have access to a horse and cart, as in Kouboura’s case, further delaying their care.

“I would like to see a world without fistula,” says Minister Kabaou. “We need more centres, more equipment, but most importantly a way to evacuate them quickly.”

In Madara, Kouboura used the approximately $100 she received from Solidarity for her reintegration to buy oxen for her family as an income-generating activity. Her father, Harouna Moutari, says he supports his daughter’s efforts to help other village women.

“I am so proud of my daughter,” he says. “Her talking about what has happened to her has helped prevent others from getting this injury.”

— Angela Walker