News

Adama's Story: An Excerpt from 'Moving Young'

- 23 August 2006

News

More than ever, young people move. Over the past few decades, political, economic, social and demographic changes have uprooted many people and stimulated migration to cities and abroad. The growing volume of trade, faster and cheaper transport, and easier communication have encouraged more young people to migrate within and across national borders. The following tale of Adama’s perilous journey in search of a better life is one of ten stories that are featured in Moving Young, a companion to the , which focuses on women and international migration. Both reports launch 6 September 2006.State of World Population 2006

***

His life had no stories. Adama S. was born in Ouagadougou, the capital of Burkina Faso, in 1981, and he never went to school. His father grew millet, corn and tapioca on a very small piece of land, barely enough to feed the family. At twelve, Adama started working as an apprentice at a mechanical workshop; three years later, he was able to fix electro-generating equipment. He probably would have stayed there for a long time if his boss hadn’t died.

The workshop closed. Now unemployed, already twenty years old, he started to wonder what he was going to do with his life. He had heard so many stories about relatives and neighbours who had gone to Europe, and how well they were doing. He had saved 200 euros: his decision seemed obvious.

First, I applied for a visa at the French Embassy, but they wouldn’t give it to me. What I wanted was to go to Europe, I didn’t care where. I was told that first I had to go to Spain, because it’s the only European country with an African border, and from there you can go wherever you want.

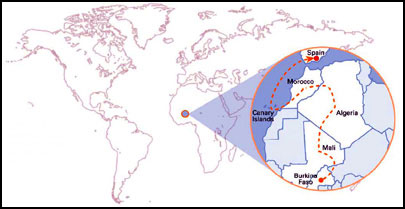

The trip got off to a good start. At the beginning of 2002, Adama bought a bus ticket to Bamako, the capital of Mali. He slept in the station for a few days, and found out that he should take another bus to Gao; there, for a hundred euros, he got a ride with a van that would carry him across the Sahara to Tamanrasset, Algeria. The journey took five nights. During the day, he and the other twenty passengers hid in caves and waited for sunset.

He was still far away from Morocco: he had to go all the way through Algeria, travelling by night, hiding by day. Sometimes he walked, sometimes he could hitch a ride by truck. Sometimes, he stayed without transportation for four of five days in an oasis, always fearing the police. It took him almost two months to cross the desert and the Atlas Mountains, and reach the Moroccan border. There, smugglers took him across the border; after four nights of unbearable walking, he arrived at Oujda. Then a bus took him to Nador, the Moroccan city near Melilla.

Melilla is a Spanish territory on the African continent separated from Morocco by a wire mesh fence. Every night, Adama would walk along the fence, looking at Europe (so near, so very near), trying to think of a way in. He knew that some had jumped, but that didn’t seem so easy. Three years later, migrants would invent the avalanche technique, which involves hundreds of people throwing themselves together against the fence; in those days however, jumping was an individual endeavour.

Once he got too close, and the Moroccan police arrested him and deported him to Algeria. Adama made his way back into Morocco, only to be deported again two months later. Adama felt defeated. He had run out of money long ago. It was the olive harvesting season; Adama worked for two months and got enough money to go back to Morocco. But this time, he headed to Rabat. The fence at Melilla seemed insurmountable and he wanted to try the water route, by the famous pateras, single-motor, ten-metre long, very precarious vessels.

In Rabat, I spent a year sleeping on the streets, eating from the garbage. I didn’t have a dime, I knew nobody, I couldn’t get a job. Not even the Moroccans had jobs. I suffered a lot. I wanted to go back to my country, but I needed money for that too.

One day, desperate, Adama turned himself over to the police in an attempt to be sent home. An officer shouted that if he wanted to go back, he’d better do it himself. Adama thought he had reached the bottom.

In my country, at least I was able to eat. I felt very miserable. But I kept fighting, because I had to make a life for myself.

Then his luck started to change. He met a Malian who offered him a place in his room and put him in touch with a man in the patera business. This man, a Ghanaian, proposed a deal: if Adama could find twenty clients willing to pay between 1000 and 1500 euros, he could travel free. Around that time, Adama was finally able to call home to let his parents know he was still alive, if still in Africa. It was then that he learned that his father had died.

My mother told me he had been poisoned, but I never found out what really happened, because I could never get back to my country.

At first, Adama couldn’t find any clients; nobody trusted him. Little by little, however, he made his reputation and, by the end of 2004, Adama had already sent forty travellers. He had earned his trip. He had spent two years waiting for this moment.

From Rabat, a truck took him and twenty other men to a shelter in the desert. There, they had to wait until the police officers, who had been bribed by the smugglers were on duty. They spent several days without water. Adama saw others drink their urine but he couldn’t do it. Then, one afternoon, they were all put back in a truck that took them to a secluded place on the Atlantic coast. The smugglers made them throw away their identity papers before getting on the boat.

On the beach, in the moonlight, Adama had another shock: the Moroccans who worked for the smugglers robbed them of everything they had, money, watches, clothes. Adama tried to defend himself and one of them cut him in the hand with a knife. Wounded, he got in the patera. His shirt and his shorts were all he had left in the world, but at long last he was sailing to Europe.

The captain was a fisherman from the Gambia; the trip was his pay. He asked Adama to watch the compass. They had to keep a heading of 340 degrees – if they went off course they were dead. He said the trip was easy and they’d be in the Canary Islands in less than a day. Even if the boat was wrecked, he said, he and Adama would survive: they were the only ones who had plastic fuel containers to float on until someone came to their rescue.

That calmed me down. At least I would survive. But I was very nervous anyway: I had never seen the sea before.

***

Stay tuned: The rest of Adama’s story – and the stories of nine other young people affected by migration – will be released as a special youth edition of the State of World Population 2006. The main report, A Passage to Hope: Women and International Migration, discusses the rise in female migration and the implications of this for individuals, families, communities and countries.